Period Homes, Language and Architecture by John Tittmann AIA

This essay originally appeared in the July 2004 issue of Clem Labine’s Period Homes

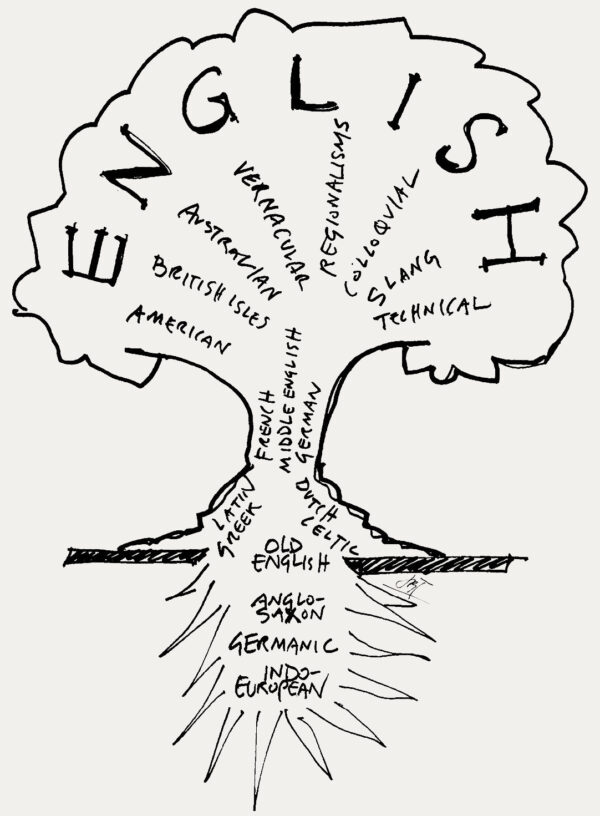

Architecture can be likened to a tree:

It has historical roots. It has many branches. And the roots provide nourishment to the living branches. History is present, not past. Architecture, like a tree, is living. The branches of architecture – where we currently practice – are inextricably connected with its history – its roots.

The English Language is also like a tree.

Like the “Tree of Architecture,” this tree also has historical roots. It too has many branches, and its roots continue to inform the present. Our language, English, embodies its history in the current spoken word. The deepest Indo-European root words are still part of some of our everyday words. It can be said that the roots have actually formed the branches we know today.

The “Tree of Architecture” works that same way. Both of these “trees” are formal systems. These “trees” exist as a set of rules, signs, and symbols like sentence structure, syntax and verb conjugations. These rules make form possible. The ability to express is provided by the armature of these languages.

Talk is different from language.

The language of Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address is memorable. Talk, is, well, just talk. Language – its system of conventions enables communication. If you can’t understand my words, you won’t get my drift.

So you see, without language, words are just formless stuff. Here the English architect Edwin Lutyens links language and architecture:

“I require of a building, as of an individual, that a statement should be made gracefully, perhaps with distinction and humour. Many modern buildings, to me, are just shouting very loud and quite unintelligibly. I catch a phrase here and there, recognizing a scrap of English or Italian, may be. There is vitality, heaps of it. But there seems to me no grammar and little sincere effort at style.”

Architects today, like Lutyens not so long ago, are intensely interested in creativity. Architects have always wanted to make it new. Creativity making it new, Lutyens seems to be saying, is the artful use of the language. In other words, creativity occurs not in the invention of a new language but in the inventive use of an existing language.

With rule comes language; with language comes creativity.

Creativity flourishes when there’s something to push around, something to push against. Artfulness is the gentle and inventive bending of the rule.

Let’s go back to language. Good writers have never been straight-jacketed by rule of language. Emily Dickinson wrote about bending the rule in a poem called, “Tell all the Truth but tell it slant” (at least I read it this way):

Tell all the Truth but tell it slant --

Success in Circuit lies

Too bright for our infirm Delight

The Truth’s superb surprise

As Lightening to the Children eased

With explanation kind

The Truth must dazzle gradually

Or every man be blind --

Dickinson here artfully bends language as a way to express truth. If “truth” is expressed too quickly, it will blind. We need truth brought in slowly; we need the context of the standard, the expected. We can’t just go straight; we need the slant and the bent rule.

For the most part, this fundamental aspect of art is not part of current discourse. Popular criticism in architecture tends to blame the “language” itself, and not the artistry of the speaker.

But the “Tree of Architecture” is not the problem.

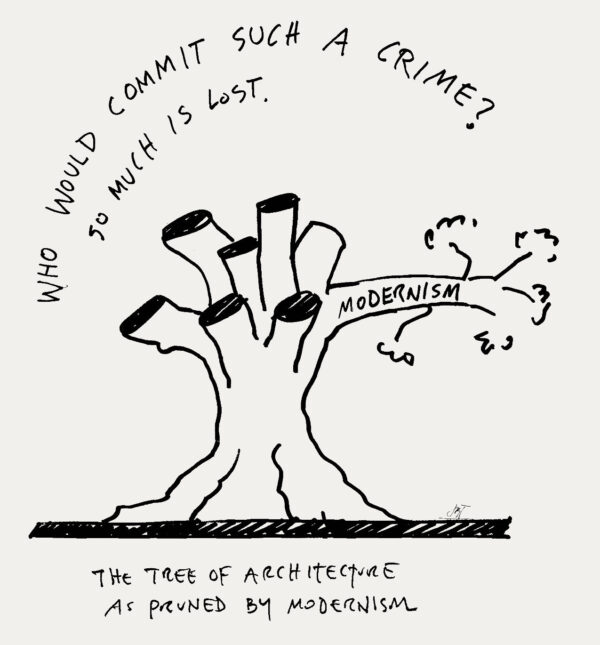

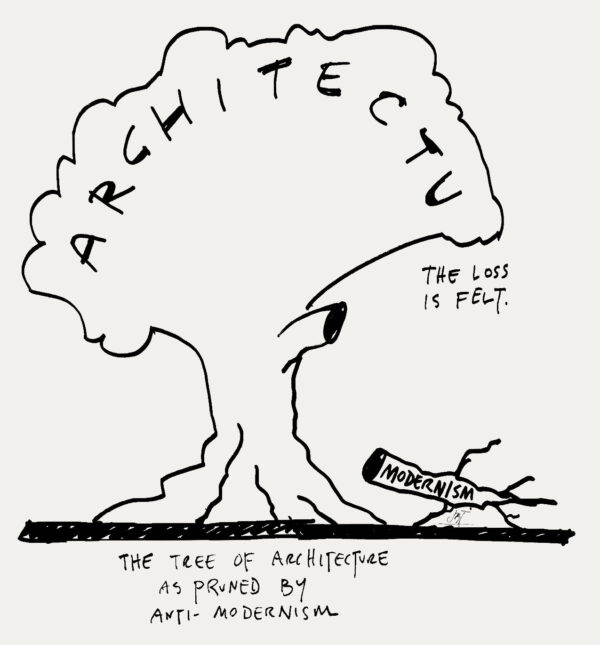

“Fixing” architecture by aggressively pruning most of its branches won’t give us a revitalized architecture, as some argue. It merely leaves a misshapen, wounded tree (by the way, it’s also misguided to harshly prune the tree in other ways – all the branches contribute to the tree of architecture’s vitality):

So what are we to do?

This is what I think: Measure architecture by its artfulness, by the skill of the making, by it’s “slant-ness,” by its mastery of the grand set of rules and conventions. Architecture is its history and traditions. The straight-jacket is not the language, as so many have claimed, but the lack of language. (And while we’re at it, shun the clichés of progress and contemporary-ness and moral superiority.)

Architecture is an art.